The NHL says they’ll do one thing and then not follow through.

Hockey isn’t for everyone, and it’s especially not for minorities. Well, at least not for now. Here are three reasons why.

Racist events continue to happen in hockey at all levels

I won’t go into detail about the laundry list of racist incidents at hockey games, but it’s not just the professional level either. There are such incidents at youth hockey games as well.

In 2018, four male Chicago Blackhawks were ejected from the Blackhawks vs. Capitals game at the United Center for shouting “basketball, basketball, basketball” at a visiting Black player, Devante Smith-Pelly, a former forward for the Washington Capitals. Smith-Pelly became a Stanley Cup champion with the Capitals in 2018 and retired from the NHL in 2022. The Scarborough, Ontario, native represented his native Canada and won a gold medal at the 2009 World U-17 Hockey Challenge and a bronze medal at the 2012 IIHF U20 World Championship.

I’m glad the Blackhawks organization took immediate action after the incident. But prevention is equally as important as action. It has been 66 years since Willie O’Ree broke the color barrier with the Boston Bruins in 1958. O’Ree became the first Black man to play in the NHL.

After the incident, Smith-Pelly told the AP: “[O’Ree] had to go through a lot, and the same thing has been happening now, which obviously means there’s still a long way to go … If you had pulled a quote from him back then and us now, they’re saying the same thing, so obviously there’s still a long way to go in hockey and in the world if we’re being serious.”

The NHL was allegedly forced to confront its own reaction to racism. In case you forgot, Milwaukee Bucks players reportedly decided not to take the court for an NBA postseason game in 2020 to protest the officer-involved shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The Milwaukee Bucks inspired other players and leagues to do the same. That said, the sports world confronted police violence against Black people, including the NHL, who played a 27-second moment of reflection before a Boston Bruins and Tampa Bay Lightning game and lit up a jumbotron with the words “End Racism.”

The NHL’s reaction to racism was tolerable, but there was no formal acknowledgment of Jacob Blake at the game between the Colorado Avalanche and Dallas Stars. The Avalanche postponed the game against the Stars, but that’s arguably a weak decision. The shooting of Blake was just one of many shootings in the United States, but the NHL was fairly silent.

The NHL has a platform to tell the public about the games, charities, etc. They could be better by educating the public about race relations instead of waiting for racial incidents to happen to minority players. They won’t actually end racism (and no one can, not even a U.S. President), but they can increase their diversity and anti-racism efforts and achieve a shift in hockey culture, both on and off the ice.

Asian and Black communities have a long history of shared solidarity, including NHL players of one or both ethnicities.

Asian and Black communities are often portrayed as conflicting with each other in America. But, in reality, Asian and Black communities have a long history of organizing with each other.

Both Asians and Blacks have shared stories of loss, struggle, change, and hope. As an Asian American, I can vouch for the solidarity between both sides. The solidarity’s historical roots date back to 1955 with the Bandung Conference, where representatives of people from Asia and Africa came together to talk about what decolonization was going to look like for both races.

The solidarity has made shockwaves in the NHL, as there are NHL’ers who are Black, Asian, or both. Take, for example, Joshua Ho-Sang, who’s currently an unrestricted free agent, an NHL’er who was born in Toronto, Ontario, to a Jamaican father of African and Chinese descent and a Chilean mother of Swedish and Russian-Jewish ancestry. Ho-Sang was best known for his tenure with the New York Islanders after being drafted 28th overall in the first round of the 2014 NHL Draft.

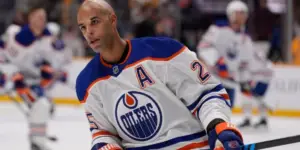

There are also NHL’ers who are Middle Eastern. For example, Nazem Kadri, a forward for the Calgary Flames. Nazem is a London, Ontario, native of Lebanese descent, as his grandparents were born in Kfar Danis, Lebanon, and moved to Ontario when Nazem’s father, Samir, was four years old. I’m pretty sure Nazem can talk about racial matters, especially after St. Louis Blues goaltender Jordan Binnington threw an empty water bottle at him in the 2022 NHL Playoffs.

The NHL should focus on building a movement and not just having a moment. As of 2022, the NHL has 54 active players who are Arab, Asian, Black, or Indigenous, which is about seven percent of the league. That’s a significant increase since Black players like Anson Carter played professional hockey. The NHL shouldn’t make diversity hires just to make diversity hires. Instead, the NHL should hire a diverse pool of people based on their talent, as they should expect the best — and this should apply to both players and employees.

Change is happening slowly but surely, but the NHL is moving in the right direction.

The NHL’s Pride Nights are publicity stunts.

The NHL’s Pride Nights aren’t as black and white as you may think they are. Sure, Pride Nights celebrate the LGBTQ+ community, but at the same time, namesake nights come with incidents, issues, and the like.

The Philadelphia Flyers were reportedly the first NHL team to shine a bad light on Pride Night when Russian defenseman Ivan Provorov refused to wear a Pride warmup jersey for religious reasons in January 2023. Provorov’s controversial decision became a trend throughout the league as other NHL’ers, such as San Jose Sharks goaltender James Reimer and Florida Panthers brothers Eric and Marc Staal, followed suit. Plus other NHL teams opted not to wear Pride warmup jerseys.

To add fuel to the fire, the NHL banned Pride Tape in the Summer of 2023. As you might’ve guessed, the NHL’s decision set off a backlash from NHL players and fans alike. As a journalist by trade, I understand others’ religious, political, and personal reasons, but I believe the league’s decision was a step backward. I’m aware some players disagreed with the ban, but they respected the rules, while some announced they’d use the Pride Tape anyways. To each their own.

NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman told ESPN Radio’s UnSportsmanlike: “What happened last year was that the issue of who wanted to wear a particular uniform on a particular night overshadowed everything that our clubs were doing. So what we said, instead of having that distraction and having our players have to decide whether or not they wanted to do something or not do something and be singled out, we said, ‘Let’s not touch that.'”

“Anything around the game, anything off the ice. Our teams and our players are continuously encouraged to give back to the communities and get involved in the causes that they find important … But what I think we did is we took the distraction away. And so now the concentration can be on the causes that we want to highlight.”

By taking Pride-themed clothing and accessories out of the equation, the NHL sends a message to everyone. It’s fine, we can take out the distractions, and we’ll show support for the LGBTQ+ community. Go to the Pride game and pregame festivities, and you’ll help fundraise local LGBTQ+ charities.

I’ve co-hosted a Pride Night podcast episode in 2021. I’ve worked with people who are either for or against LGBTQ+ rights. I do respect a person’s point of view. But, at the same time, Pride Nights exist to tell LGBTQ+ fans and players they’re safe, accepted, and loved in arenas.

Luke Prokop became the first NHL player to come out as gay in 2020, just like Michael Sam became the first openly gay football player to be drafted in the NFL in 2014. But how much diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) progress has been made in sports since those two historic moments? Think about it.

Discover more from Inside The Rink

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.